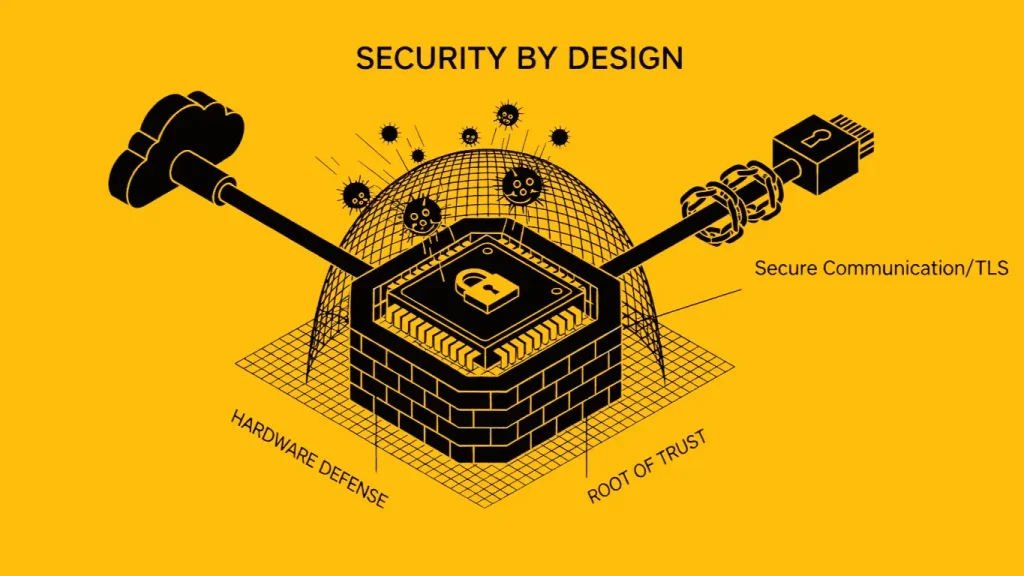

For technical leadership, security can no longer be a patch applied just before launch or a perimeter defense added as an afterthought. It must be a foundational architectural property.

With embedded devices—from industrial controllers to smart home sensors—facing direct physical and network exposure, implementing security at the chip level is non-negotiable.

Security by Design means treating vulnerability mitigation as a core requirement from “Phase 0.” This proactive approach prevents the catastrophic financial and reputational costs of post-launch breaches and mandatory product recalls.

Pillar 1: Hardware Root of Trust (The Foundation)

The security chain is only as strong as its first link. The Hardware Root of Trust (RoT) establishes an unforgeable, immutable identity for the device, providing the bedrock for all subsequent cryptographic operations.

- Secure Elements (SE) & TPMs: We leverage specialized chips (SE or TPM) or internal MCU Hardware Security Modules (HSM) to securely store private keys, provisioning data, and unique device identifiers. This physically isolates sensitive material from the main application processor.

- Secure Boot: This acts as the gatekeeper. It is a hardware-enforced process that validates the digital signature of the bootloader, OS, and application firmware. If the signature doesn’t match the known Root Key, the device refuses to execute, effectively blocking unauthorized or malicious code injection.

- Tamper Resistance: We design physical controls (e.g., disabling JTAG ports post-production, secure storage protection) that detect intrusion attempts. In extreme cases, these systems can irreversibly “zeroize” (erase) cryptographic keys to prevent theft.

Pillar 2: Firmware and OS Hardening (Minimizing Attack Surface)

The software running on the device must be architected to minimize the attack surface and enforce a strict separation of privileges.

- Principle of Least Privilege: Utilizing the RTOS or OS kernel to create secure memory domains. This ensures that a compromise in non-critical application code cannot leak into critical services like cryptography or sensor drivers.

- Input Validation & Code Safety: Implementing rigorous coding standards to prevent common exploits like buffer overflows. This often involves using modern, memory-safe languages (like Rust for embedded) or strict compiler checks.

- Monotonic Counters: These immutable hardware counters prevent “rollback attacks.” Even if an attacker has a valid, older firmware version with known vulnerabilities, the device checks the counter and refuses to install it, ensuring the security state only moves forward.

Pillar 3: Secure Communication & Lifecycle Management

Security extends beyond the device border. It must cover data transmission and product maintenance over a decade-long lifecycle.

| Security Aspect | Implementation & Protocol | Risk Mitigation |

| Data in Transit | Enforcing TLS/DTLS for all MQTT, HTTP, or CoAP communication. Utilizing unique X.509 certificates for mutual authentication. | Prevents Man-in-the-Middle (MiTM) attacks and eavesdropping. |

| Secure Updates | Robust OTA mechanisms with A/B partitioning and cryptographic signing. The device verifies the update against the Hardware RoT. | Protects against malicious firmware injection and ensures non-bricking rollbacks. |

| Key Management | Using approved key management systems for lifecycle tasks (e.g., rotating certificates). | Eliminates the risk of hard-coded credentials/passwords in firmware. |

Investing in Long-Term Viability

Investing in Security by Design is the only way to meet modern regulatory standards (like ETSI EN 303 645 or the EU Cyber Resilience Act) and safeguard the long-term viability of deployed systems.

Security is not a feature list; it is a design philosophy. Don’t retrofit security onto vulnerable hardware—build resilience from the silicon level.